JULIAN HOEBER

Paris

11 September – 8 November 2014

Julian Hoeber’s third solo exhibition at the gallery features a series of new paintings, an architectural intervention in the form of crown moldings, as well as a selection of sculptures, including a door leaning against the wall, a chrome tube chair with a twist, and two cameras on a tripod.

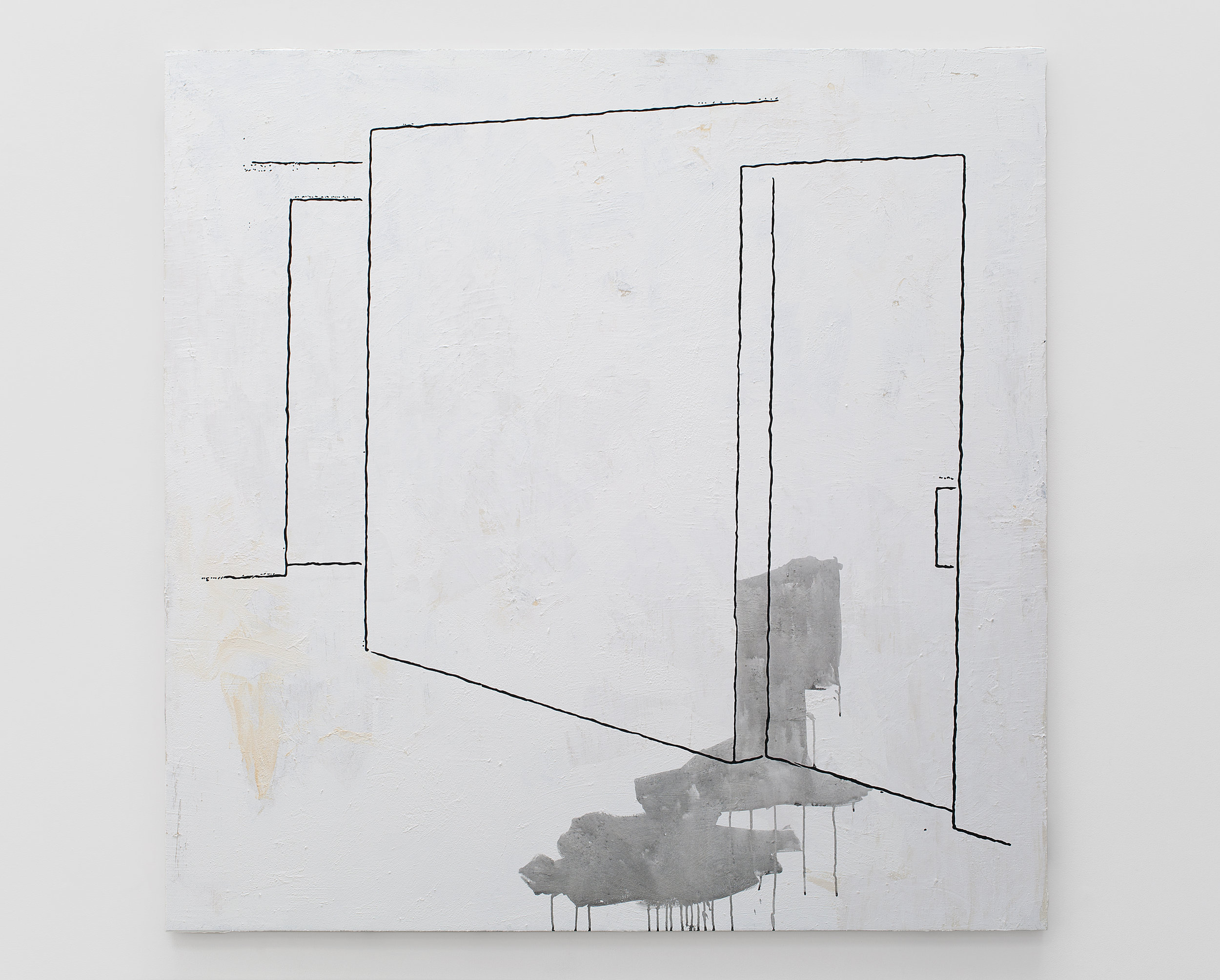

Over the years, space and psychology have crystallized as the main issues in Hoeber’s practice - the body as a space that contains or is the self, architecture as a space that the self occupies, and artworks that represent or explore the problems of those structures. Nearly all of Hoeber’s earlier bodies of work, from bronze heads full of holes, to the disturbing phenomenological architecture of Demon Hill have explored these issues. Even the seemingly abstract Execution Changes paintings can be read as imaginary spaces reminiscent of doors, passages or light sources.

With this new exhibition, Julian Hoeber moves these ideas into new forms while clarifying and reinforcing them. While many of the earlier Execution Changes paintings related to architectural form, the variants in this exhibition show a clearly representational sky and thereby implicitly include the viewer’s body.

Hoeber makes his point even more distinct with three large paintings included in the exhibition. The source material for these paintings of interiors are erotic cartoons, but with all of the characters and text removed. Clearly events have occurred in these spaces, but what remains is architecture and something that resonates as a crime scene.

The sculptural works displayed offer us other entries into Hoeber’s preoccupations: a distorted door leans against a wall like a McCracken slab; It’s Funny Because It’s True is a play on modernist design gone wrong. Hoeber designed a chair based both on Marcel Breuer’s modernist furniture and on a commode toilet. Breuer’s tubing is now so commonplace, that the same technique is used to produce the most banal furniture and even medical equipment. Hoeber’s chair takes on an even more perverse quality: the seat has a hole in it like a toilet, but the hole is also the inside of a head, poetically hanging from the bottom of the seat.

Finally, Hoeber has crafted an exquisite surveyor’s tripod from walnut and brass. Atop the tripod are two sculptures of cameras through which the show can be seen, though distorted and inverted and from multiple perspectives. The camera becomes what it etymologically signifies, a room that contains what is seen through it.

Overall, Hoeber’s exhibition is built from the repetition of forms in space, and the breaking or perversion of the systems of repetition, in order to inflect the works with sensations of memory and resonance. Over time Hoeber’s different bodies of work have pursued various effects, but with similar methodology. The totality of the works, with all their different effects, speak to one another over space and time.